Written by Anibal Ballarotti and Jesus Berumen for Progressive Dairy

Training and working with many A.I. technicians – both herdsmen, inseminators and professional inseminators – reveals common mistakes that should be avoided. The following are seven points that can make or break insemination results.

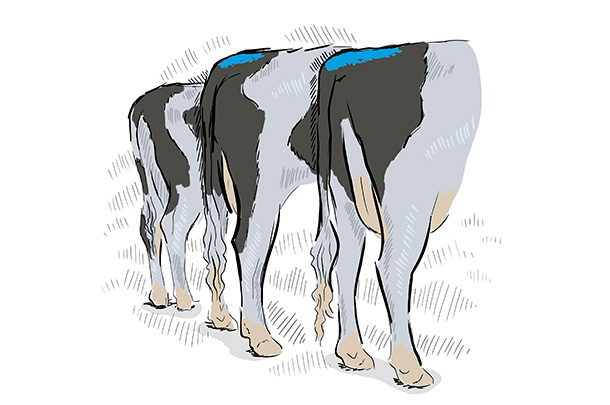

1. Breeding animals that are not in heat

We need to be sure the cow to be bred is truly in heat. Literature indicates as high as 20% of cows bred are not actually in heat. Research also shows that a skilled A.I. technician can achieve 65% to 75% heat detection efficiency. Failure to accurately detect cows in heat is the most common and expensive problem of A.I. programs. Further, research indicates heat detection efficiency can be lower than 50% in many herds. When working with cows of uncertain status, a good breeder will check the current and previous information about the animal’s history, as well as check for secondary signs of heat. To make a final breeding decision, it is also helpful to perform a transrectal palpation of the cow, looking for presence of mucus and uterine tone.

2. Not consistently painting all the animals

Another factor that can make the breeding decision harder than it should be is failure to consistently paint every single cow, every single day, as it should be done. In instances of overstocking animals or when there are no headlocks for the whole group, it’s common to have loose cows that do not receive their tail painting. As a consequence, they can result in confusion in the next day(s) when A.I. technicians read and interpret the marks. The problem becomes how to understand faint evidence of paint or none at all due to lack of painting.

3. Incorrect semen handling before thawing

When manipulating semen in the nitrogen tank, the A.I. technician should keep straws not intended for immediate use below the frost line in the neck of the tank. Although the temperature of liquid nitrogen is -320°F, there is a temperature gradient in the neck of the tank. According to Dr. Joe Dalton (University of Idaho), a tank with a neck tube measuring around 6-inches long may have a temperature of -103°F in the middle of the neck (about 3 inches below the top), while the temperature at around 1 inch below the top may be 5°F. Research trials have shown reduced sperm motility due to injury at temperatures as low as -110°F. So, stored straws constantly exposed to temperature variation will suffer sperm injuries that will reduce semen fertility.

4. Incorrect semen handling during thawing

The temperature of the water bath for thawing semen for A.I. is recommended to be between 94ºF to 98°F. It should always be checked, preferably with a digital thermometer. This warm-water temperature results in greater sperm survival when compared to thawing semen in cold water or just thawing in the air. Both cold water and air thawing makes the thawing process occur at a slower rate, exposing sperm to injury. Water, at the recommended temperature, quickly transforms sperm and avoids injury to cells. Also, it’s important to prevent direct straw-to-straw contact during thawing. This is to avoid decreased post-thaw sperm viability as a result of straws freezing together. It is best to thaw no more than five straws at one time in each water bath. This helps to keep the temperature at the recommended range.

5. Incorrect semen handling after thawing

After thawing semen straws in a warm bath for the recommended time (it varies according to each different stud but, at ABS, we recommend at least 35 seconds), dry off the units in a warm and highly absorbent paper towel to protect them from excessive light, wind or temperature variation, moving the units into the insemination sheaths previously loaded into the gun warmer. Once inside the gun warmer, with verified batteries working, finish the A.I. gun assembly in order to maintain thermal protection of the straw. This thermal protection is necessary during all the steps from thawing, assembly and transport to the cow to be inseminated. Lastly, but no less important, is to use a timer to make sure semen will be placed into the cow in less than 15 minutes for conventional or beef semen and less than seven minutes for sexed semen.

6. Use appropriate hygiene procedures to avoid contamination

Breeding sheaths should be stored in the original package until used. After the A.I. gun is assembled, it must be protected from contamination and thermal shock. The vulva area must be wiped clean with a paper towel. This is important to prevent the interior of the reproductive tract from becoming contaminated and possibly infected. A folded paper towel can be inserted into the lower portion of the vulva. The A.I. gun can then be placed between the folds of the towel and inserted into the vagina without contacting the lips of the vulva. After placing the A.I. gun, the folded towel should be removed to not keep open the lips of the vulva.

7. Proper site of semen deposition

In order to avoid the possibility of entering the urethral opening on the floor of the vagina, the A.I. gun should be inserted into the vagina upward at a 30-degree angle. The target for semen deposition (the uterine body) is relatively small. Accurate placement of the semen is one of the essential skills involved in the A.I. technique. A.I. technicians can identify this target area by palpating the end of the cervix and feeling the tip of the A.I. gun. Deposition of the semen still in the cervix or randomly in the uterine horns may result in lower conception rates. The plunger for semen deposition should be held down about five seconds to maximize the amount of semen delivered.

Whether you are a herdsman inseminator or a professional A.I. technician, consider attending a retraining course once a year to review heat detection skills, semen handling and A.I. technique to keep improving performance. Taking extra care during all A.I. steps can improve the efficiency of any dairy’s reproductive program.

Jesus Berumen is a technical service specialist at ABS Global Inc. Anibal Ballarotti is a consultant at ABS Global.

Illustration by Corey Lewis.

Originally published in Progressive Dairy